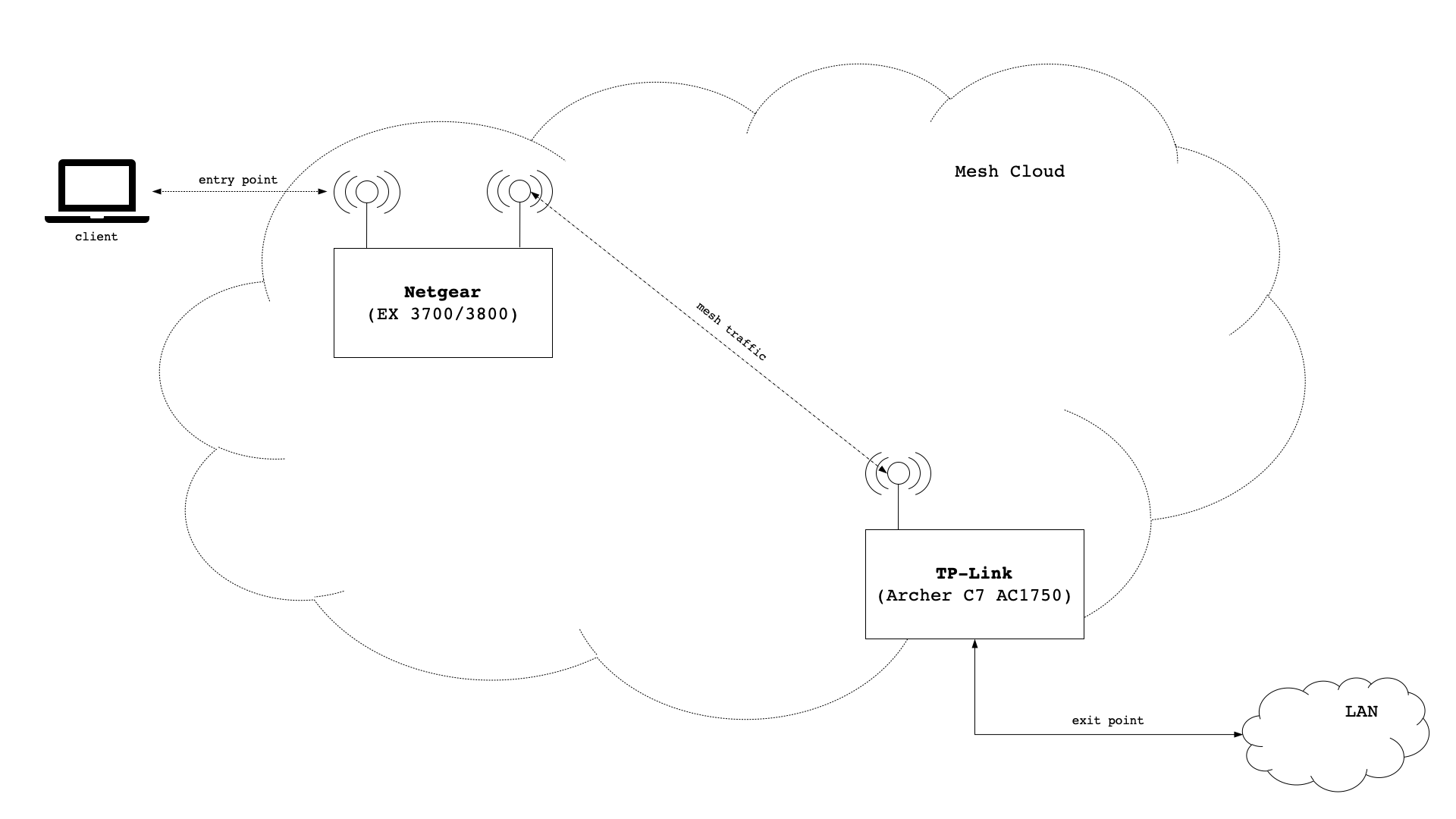

In this second blog post we will switch from a username/password authentication to a certificate based authentication using EAP-TLS. We will go into detail on the x.509 certificates employed for both the VPN initiator and VPN responder.

Changes to previous setup

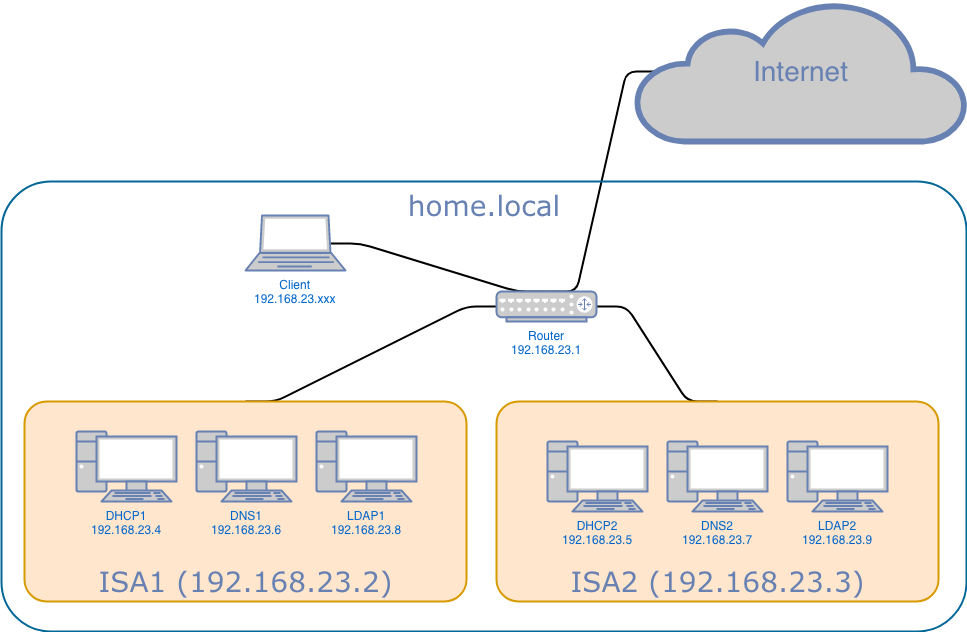

In the first part of this blog post we drew a big picture, made some assumptions, defined preconditions and agreed on a network setup. All these points actually won’t change for the second part, as the only thing we’re changing is authentication. In other words we only change the way how a client (the VPN initiator) authenticates itself to the server (the VPN responder) and vice versa.

Extensible Authentication Protocol

When talking about EAP-TLS we’re using a framework called the Extensible Authentication Protocol, which is commonly used in network communications and also is a big part of the 802.1x standard.

What happens in a nutshell is that upon establishment of a VPN connection, TLS handshakes are being used to mutually authenticate client and server. While this method consumes a lot of extra messages during key exchange (~6 to 10 extra IKE messages), it has a lot of advantages. One of those advantages is the authentication against an AAA backend (a RADIUS server). Another advantage is that all modern operating systems for mobile and desktop devices support authentication via this method.

Certificates

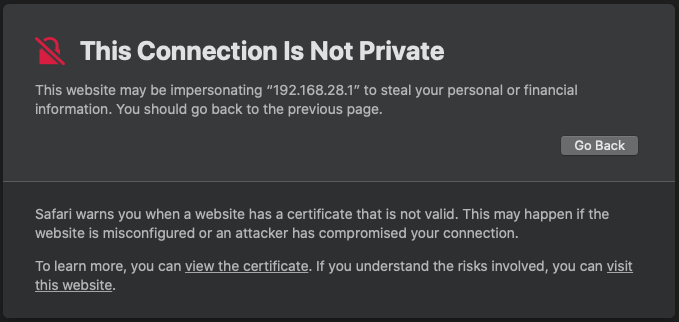

The first thing we need to clarify is how our certificates can be verified by both the VPN initiator and the VPN responder. For that to happen, certificates must be derived from a certificate authority that everybody trusts. While it is of course possible to obtain a certificate from a certificate authority that is represented in Mozilla’s, Apple’s or Microsoft’s root store, it is not necessary. Besides the associated cost for such certificates, we don’t actually need anybody to trust our certificates. Only actual parties involved in our VPN connection need to trust our certificates.

Long stories short – we will use our own root certificate authority to issue our certificates. Ideally we actually don’t even use the root certificate authority, but an intermediate certificate authority to issue our certificates.

+-------------+

| |

| ROOT CA |

| |

+------+------+

|

v

+----------+----------+

| |

| INTERMEDIATE CA |

| |

+---------+-+---------+

| |

| |

| | +------------------+

| | | |

| +--->+ HOST CERTIFICATE |

| | |

| +------------------+

|

|

| +--------------------+

| | |

+----->+ CLIENT CERTIFICATE |

| |

+--------------------+

Host Certificate Deployment

As stated above, the VPN responder needs not only the host certificate, but only the certificate issuing chain for verification. Let’s have a quick look at those parts of the directory structure that is important on our VPN responder (our OpenWrt router):

/etc/ipsec.d

├── cacerts

│ ├── tinkivity-rootca.pem

│ └── tinkivity-stepca.pem

├── certs

│ └── servercert.cert.pem

└── private

└── servercert.key.pem

O.K. – but what goes where?

cacerts

In this directory we put the root certificate as well as all other intermediate certificates. We need to know that strongSwan only reads the first certificate in every certificate file (i.e. .pem file), so placing one full-chain certificate file will do us no good. Instead we will put one certificate for every certification authority in our chain in that directory. In our case this directory will contain two certificates. Upon start the ipsec daemon will automatically load all certificates it can find in this directory. That means that no configuration entries are needed to make ipsec aware of certificates in that folder.

certs

As part of the configuration in /etc/ipsec.conf we can define certificates to be used (i.e. via left|rightcert statements). This folder contains such certificates and in our case it will contain our host certificate.

private

For every certificate that we use as part of our /etc/ipsec.conf configuration, a private key is needed. This folder will contain one private key for every corresponding certificate mentioned in the left|rightcert statements in our configuration. In our case this directory will contain the private key of our host certificate.

For strongSwan to properly load the private key (including application of the passphrase that protects it), the following entry is needed in the /etc/ipsec.secrets configuration:

# /etc/ipsec.secrets - strongSwan IPsec secrets file : RSA servercert.key.pem "INSERT PASSPHRASE HERE"

Host Certificate Generation

In general we follow the common recipe for generating any x.509 certificate. We create a private key, a certificate signing request and we sign the certificate.

Private Key

We choose RSA as algorithm and create a 4096 bit long private key that we protect by a password. Rather than using the legacy genrsa command in openssl, we go with the newer genpkey command, as it allows for better fine-tuning. We do not put the passphrase on the command line, but define a file (passphrase.txt) that we include into our command.

andreas@intermediateca ➜ ~ openssl genpkey -algorithm RSA -aes-256-cbc -pkeyopt rsa_keygen_bits:4096 -pass file:passphrase.txt -out servercert.key.pem

Certificate Signing Request

Because we want to limit the length and complexity of our command line, we use an openssl configuration file to determine what we want in our certificate.

[req] prompt = no distinguished_name = req_dn req_extensions = req_ext [req_dn] CN = vpn.example.com [req_ext] subjectAltName = @alt_names [alt_names] DNS.1 = vpn DNS.2 = vpn.example.com DNS.3 = internalhostname DNS.4 = internalhostname.lan.local

The canonical name (CN) must be set to match one of the subject alternative names (as shown in lines 13-16 above). Moreover, there must be match between one of the subject alternative names and the leftid used in the configuration at /etc/ipsec.conf for the certificate to be useful for strongSwan. Eventually we issue the certificate signing request with the following command:

andreas@intermediateca ➜ ~ openssl req -new -config config.cnf -key servercert.key.pem -passin file:passphrase.txt -out request.csr

Certificate Signing

For convenience we use our smallstep intermediate certificate authority for signing our certificate. However, we could just as easily sign our certificate directly with openssl.

andreas@intermediateca ➜ ~ step ca sign --ca-url https://acme.tinkivity.home:8443 --root /etc/ssl/tinkivity.pem --provisioner vpnserver-prov --not-after 2021-12-31T23:59:59Z request.csr servercert.cert.pem

More important than how we sign the certificate is the question what our certificate looks like? We use openssl to inspect the content of the certificate:

andreas@intermediateca ➜ ~ openssl x509 -noout -text -in servercert.cert.pem

Certificate:

Data:

Version: 3 (0x2)

Serial Number:

46:79:09:ef:cf:6a:8a:55:93:17:6c:fe:44:38:0a:89

Signature Algorithm: sha256WithRSAEncryption

Issuer: C = DE, ST = Saxony, O = Tinkivity, OU = Tinkivity Intermediate Certificate Authority, CN = Smallstep Intermediate CA, emailAddress = xxx@xxx.com

Validity

Not Before: Jan 9 14:16:05 2021 GMT

Not After : Dec 31 23:59:59 2021 GMT

Subject: C = DE, ST = Saxony, L = Dresden, street = "Musterstrasse 1, 01234 Dresden, Germany", O = Tinkivity, OU = vpn servers via manual vpnserver-prov, CN = vpn.example.com

Subject Public Key Info:

Public Key Algorithm: rsaEncryption

RSA Public-Key: (4096 bit)

Modulus:

00:cb:9a:1a:dd:28:a7:84:8e:15:e7:83:c0:64:1c:

...

<< REDACTED >>

...

b9:36:25

Exponent: 65537 (0x10001)

X509v3 extensions:

X509v3 Extended Key Usage:

TLS Web Server Authentication

X509v3 Subject Key Identifier:

90:F9:FF:02:CD:CA:5E:2F:61:43:EA:8B:CB:B0:FE:DD:7A:16:77:D4

X509v3 Authority Key Identifier:

keyid:87:32:28:49:63:29:06:79:96:13:DE:47:14:9F:EF:C0:DD:EC:4D:C3

X509v3 Subject Alternative Name:

DNS:vpn, DNS:vpn.example.com, DNS:internalhostname, DNS:internalhostname.lan.local

1.3.6.1.4.1.37476.9000.64.1:

0@.....vpnserver-prov.+jtrIkQa8-b_nzz2OU4DlffIMHmDZmhVV1R3rBBC46qo

Signature Algorithm: sha256WithRSAEncryption

4a:3a:26:fa:dc:3b:08:be:df:03:a1:cf:d7:47:e5:98:10:ac:

...

<< REDACTED >>>

...

30:25:5a:cb:94:dd:4a:24

Obviously we use a dedicated provisioner for VPN server certificates (vpnserver-prov), but other than automatic application of custom subject settings for our certificate, there is no special magic happening in the provisioner. Still, you can read my earlier blog post if you like to understand more how step ca templates can be used.

Either way, the important part of the host certificate from an ipsec point of view are the subject alternative names (line 32 above). Matching between leftid in the configuration, the Remote ID declared on the client side and one of the subject alternative names is crucial.

VPN Responder Configuration

In the first part of this blog post we defined EAP-MSCHAPv2 as authentication method.

/etc/ipsec.conf

Compared to the configuration we’ve used for username/password authentication, only a very few lines need to change. For better housekeeping (and debugging) we have renamed our connection (line 16) to rwEAPTLS. In line 19 we changed our rightid into vpn-via-eaptls and in line 20 we switched to eap-tls for an authentication method.

config setup

conn %default

keyexchange=ikev2

ike=aes256-aes128-sha256-sha1-modp3072-modp2048

esp=aes128-aes256-sha256-modp3072-modp2048,aes128-aes256-sha256

left=%any4

leftauth=pubkey

leftcert=servercert.cert.pem

leftid=vpn.example.com

right=%any4

rightsourceip=10.10.97.2-10.10.97.6

eap_identity=%identity

auto=add

conn rwEAPTLS

leftsendcert=always

leftsubnet=10.10.97.0/29,10.10.90.0/24

rightid=vpn-via-eaptls

rightauth=eap-tls

/etc/ipsec.secrets

In our previous configuration we had one line per every user that wanted to connect via username/password authentication with our VPN (i.e. myuser : EAP “mypassword”). As we don’t use usernames and passwords any more we can delete those lines. Alternatively we can leave them in the configuration, as strongSwan will disregard them on its own if they are not needed.

: RSA servercert.key.pem "INSERT PASSPHRASE HERE"

However, as mentioned above in this blog post, we need to put in the passphrase (if any) that is needed to decode the private key. If no passphrase is set for the private key, the configuration line ends after the name of the private key file (no empty quotes needed).

Client Certificate

As part of EAP-TLS clients need a certificate too. From an x.509 point of view there is no dramatic difference between a client certificate and host certificate. The same recipe as for host certificates does apply.

Private Key

Same as for hosts, we create ourselves a 4096 bit long RSA key and protect it with a passphrase. We follow the exact procedure as for the host private key above.

Certificate Signing Request

Same as for hosts, we create a configuration. What’s different this time though, is the content.

We use the canonical name to define the name of the user (line 7).

For the subject alternative names we like to get the user’s email address into our certificate. Besides DNS names, the standard for the subject alternative names extension allows to put email as value. We do that in line 13.

In line 14 we use DNS to specify what this client will be allowed to do in match of a rightid in our /etc/ipsec.conf configuration (see above). This is a very important part of the authentication. While the certificate chain helps strongSwan to verify the authenticity of the client certificate, the subject alternative name vpn-via-eaptls in the certificate will be matched to potential connections in the VPN responder side. As it happens we have defined one such connection and this will be the reason that the client will be allowed to connect.

[req] prompt = no distinguished_name = req_dn req_extensions = req_ext [req_dn] CN = John Doe [req_ext] subjectAltName = @alt_names [alt_names] email.1 = john.doe@example.com DNS.1 = vpn-via-eaptls

As for the generation of the CSR (certificate signing request), we follow the exact procedure as for the host certificate signing request.

Certificate Signing

Again, for convenience we use our smallstep ca to issue the certificate. This time we use a different provisioner that applies some different claims. However, the provisioner is not that important really, as besides administrative differences there is nothing going on that would require it. I mainly use provisioners for better housekeeping (i.e. certificate expiration claims).

andreas@intermediateca ➜ ~ step ca sign --ca-url https://acme.tinkivity.home:8443 --root /etc/ssl/tinkivity.pem --provisioner vpnclient-prov --not-after 2021-12-31T23:59:59Z request.csr usercert.pem

Client Certificate Deployment

When it comes to deployment to our client we actually don’t want to send a bunch of files (keys and certs). Ideally we want to only send around one archive that contains it all. We use the PKCS#12 format for that. Besides the private key and the user certificate, we also put our root certificate into the PKCS#12 archive.

andreas@intermediateca ➜ ~ openssl pkcs12 -export -inkey userkey.pem -in usercert.pem -name SomeFriendlyName -certfile /etc/ssl/tinkivity.pem -passin file:passphrase.txt -out john.doe.vpncert.p12 Enter Export Password: Verifying - Enter Export Password:

The export password that is asked for, is not the same as the passphrase of the private key. All it does is to protect the p12 archive during transport. With a strong export password it will be perfectly safe to distribute the p12 archive via insecure media (such as email, dropbox, etc.).

But careful! When creating a PKCS#12 archive, the private key in that archive will be stripped of its password. When retrieving a private key from a PKCS#12 archive, the private key will not be password protected.

andreas@intermediateca ➜ ~ openssl pkcs12 -nodes -nocerts -in john.doe.vpncert.p12

Enter Import Password:

Bag Attributes

localKeyID: B8 B9 AA 7E B5 A4 BC BD 91 B2 6A 8D 11 99 59 31 EC 34 30 CF

friendlyName: SomeFriendlyName

Key Attributes: <No Attributes>

-----BEGIN PRIVATE KEY-----

MIIJQQIBADANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAASCCSswggknAgEAAoICAQChH5dr3zCmsJtf

...

<< REDACTED >>

...

8rz6Fz++G18dufZ66uzObluJ/+mw

-----END PRIVATE KEY-----

Importing the user certificate

This part is specific to the operating system of the client, but typically a double-click on the file does the trick. Anyway, as our client receives and imports the .p12 archive, the root certificate, that allows that client to trust our host, is automatically being installed on the client as well.

Client Configuration

Compared to the first part of this blog post, there are actually only very slight differences in setup. The first step of configuring a new connection (go to System Preferences –> Network -> “plus sign” button), is still the same.

What happens after we click the Create button is a little different. We need to use our new Local ID for EAP-TLS, as we’re not using username/password authentication any longer.

Server Address: xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx

Remote ID: vpn.example.com

Local ID: vpn-via-eaptls

Also, when we click on the Authentication Settings button, we need to use Certificate for the Authentication Settings and we need to use the Select… button to use our imported user certificate.

Authentication Settings: Certificate

Certificate: Select... John Doe

Making a connection

That part has not changed. However, what you need to keep in mind now are the expiration dates of the certificates. By the time a user certificate expires, that user will not be able to use VPN any longer. When the host certificate expires, no user will be able to connect via VPN any longer.